Bhagavd Gita, reading, lecture, history

Many questions circulating today about spirituality—especially regarding the Bhagavad-gītā and its presence in the West—are shaped by popular misunderstandings and a lack of historical context. Narrow institutional preaching and rigid religious views often present selective narratives, cutting off broader historical and philosophical knowledge. This approach tends to prioritize group identity and alienation, rather than supporting genuine spiritual inquiry and inner development.

For those who wish to explore these topics on a deeper level, you may reserve a copy of my book, Gaudiya Esoterica: The Hidden Stream of Bhakti.

The presence of the Bhagavad-gītā and Vedānta in the West did not begin in the 20th century, nor with any single teacher or institution.

As early as 1785, the Bhagavad-gītā was translated into English by Charles Wilkins, making the text accessible to European readers. During the 19th century, German and British Indologists studied, translated, and taught Vedāntic philosophy academically. In the United States, thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau engaged deeply with the Gītā, integrating its ideas into American intellectual life.

Charles-Wikins

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

Indian teachers were already publicly teaching Vedānta and the Gītā in the West.

Swami Vivekananda lectured widely across America and Europe beginning in

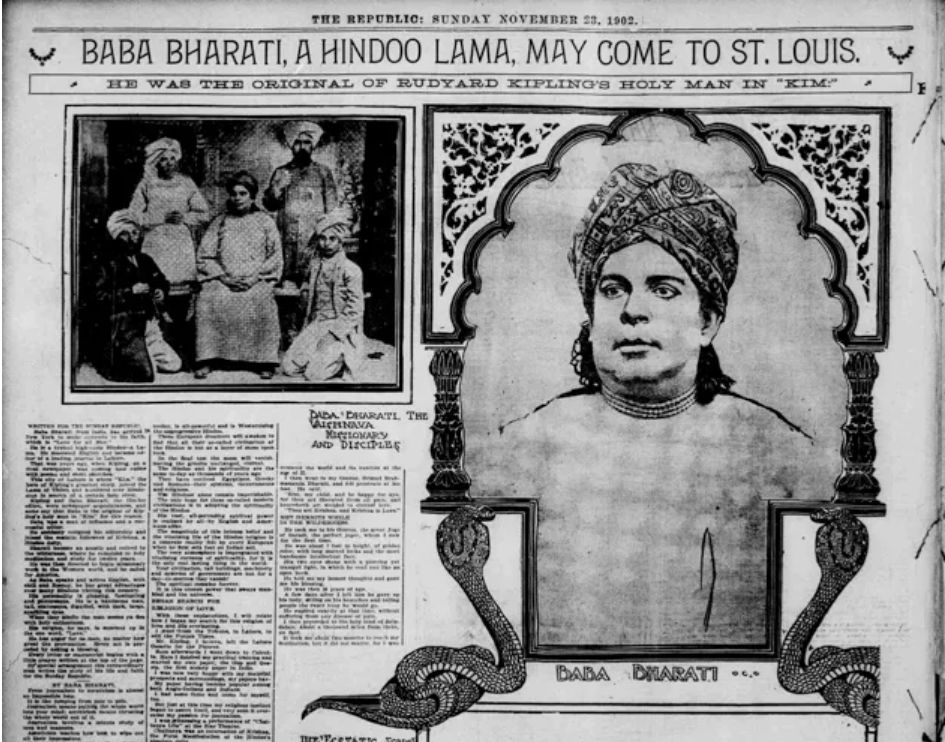

1893. Shortly thereafter, Premanand Bharati Baba arrived in

America in 1902 and played a foundational role in introducing

Kṛṣṇa-centered bhakti and Gauḍīya philosophy to the West. He authored

Krishna: The Lord of Love (1904), one of the

first English books explicitly presenting Kṛṣṇa bhakti and Gauḍīya devotional theology. Premanand Bharati initiated

more than 500 disciples and

established the first Kṛṣṇa temple in the West, over

fifty years before Swami Bhaktivedanta’s arrival. His work represents a clear and documented presence of Gauḍīya devotional practice in the Western world long before the mid-20th century.

Later, figures such as Sri Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and Mahatma Gandhi produced Bhagavad-gītā commentaries that were widely read and studied in Western universities and spiritual circles.

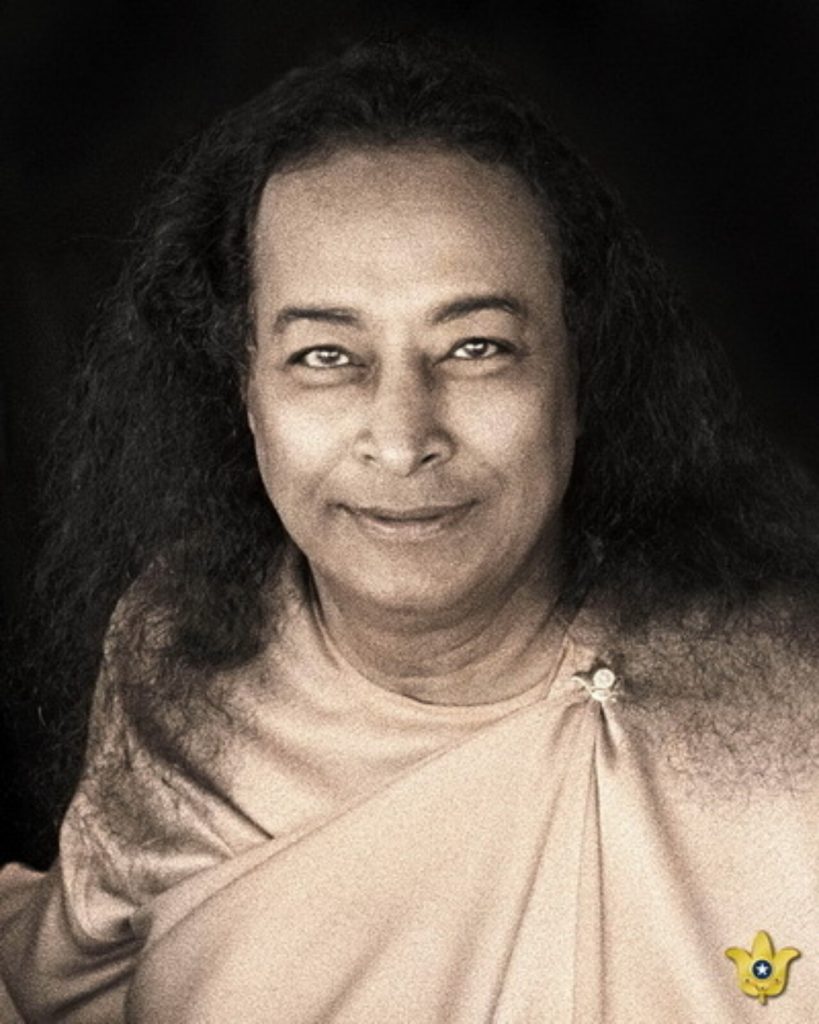

In parallel, devotional and yogic teachers such as Paramahansa Yogananda taught the Gītā extensively in America well before 1965.

Namahbrata Brahmachary delivered in-depth lectures on Gauḍīya philosophy and Vedānta at the University of Chicago more than fifty years before Swami Bhaktivedanta’s arrival in the West. His teachings addressed classical Vedāntic thought and Gauḍīya theology in an academic setting, demonstrating that these traditions were already being discussed seriously and publicly in Western intellectual institutions long before the rise of later movements.

Because of this documented historical presence, it is inaccurate to claim that Gauḍīya Vedānta or Kṛṣṇa-centered bhakti originated in the West with Swami Bhaktivedanta. Anyone who is familiar with the historical record knows that these teachings were already present, articulated, and taught decades earlier.

History does not support exclusivist narratives.

It supports continuity.

Therefore, historically speaking, the Bhagavad-gītā was already present, translated, discussed, and taught in the West long before Śrīla Prabhupāda’s mission. The philosophical foundations of Vedānta and bhakti were already established, and Gauḍīya siddhānta itself had been systematized centuries earlier in India by classical ācāryas.

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s role was not to introduce the Gītā or Kṛṣṇa bhakti to the West, but to present a specific institutional interpretation of an already-existing tradition. Recognizing this distinction allows for a more accurate and honest understanding of history.

Paramananda Dasanudas